Every time the heart beats, blood flows into, through, and out of your heart. A normal sized heart pumps about 5 -6 liters of blood through the body every minute.

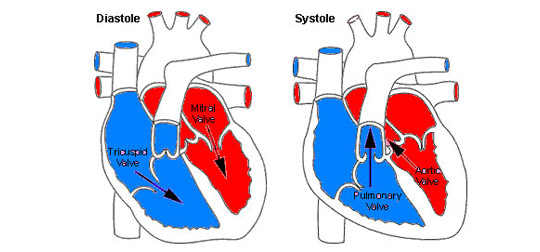

Blood is pumped through the heart in only one direction. This is possible because heart valves regulate the flow of blood in one direction; opening and closing with each heartbeat. Pressure changes behind and in front of the valves allow them to open their flap-like “doors” (called cusps or leaflets) at just the right time, then close them tightly to prevent a backflow of blood.

- Tricuspid valve

- Pulmonary valve

- Mitral valve

- Aortic valve

Blood without oxygen returns from the body and flows into the heart’s upper-right chamber (the right atrium). From there, it is forced through the tricuspid valve into the lower-right chamber (the right ventricle). The right ventricle pumps the blood through the pulmonary valve and into the lungs. While in the lungs, the blood picks up oxygen. As the right ventricle is preparing to push blood through the pulmonary valve, the tricuspid valve closes to stop blood from flowing back into the right atrium.

Oxygen-rich blood returning from the lungs flows into the upper-left chamber (the left atrium). This blood is forced through the mitral valve into the lower-left chamber (the left ventricle)—with the mitral valve sealing off to stop the backflow of blood. At the same time that the right ventricle is pumping the blood without oxygen into the lungs, the left ventricle is pushing the blood with oxygen through the aortic valve and on to all of the body’s organs.

Two types of problems can disrupt blood flow though the valves: regurgitation ( leakage) and/or stenosis (tightening).

Regurgitation is also called insufficiency or incompetence. Regurgitation happens when a valve doesn’t close properly and blood leaks backward instead of moving in the proper one-way flow. If too much blood flows backward, only a small amount can travel forward to the body’s organs. The heart tries to make up for this by working harder, but with time the heart will become enlarged (dilated) and less able to pump blood through the body.

Stenosis happens when the leaflets do not open wide enough and only a small amount of blood can flow through the valve. Stenosis happens when the leaflets thicken, stiffen, or fuse together. Because of the narrowed valve, the heart must work harder to move blood through the body.

- A weakening of the valve tissue caused by energy changes in the body. This is called myxomatous degeneration. It happens most often in elderly patients and commonly affects the mitral valve.

- A buildup of calcium on the aortic or mitral valves, which causes the valves to thicken. This is called calcific degeneration.

- An irregularly shaped aortic valve or a narrowed mitral valve. This is usually a congenital defect, which means that most people who have it were born with it.

- An infection in the lining of the heart’s walls and valves (the endocardium). This is called infective endocarditis.

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- A chest x-ray, which can show if your heart is enlarged. This can happen if a valve is not working properly.

- Echocardiography, which can produce a picture of the thickness of your heart’s walls, your valves’ shape and action, and the size of your valve openings. Doppler echocardiography (ultrasound) can be used to find out how severe the narrowing (stenosis) or backflow (regurgitation) of blood is.

- Electrocardiography (EKG or ECG) can be used to find out if your ventricles or atria are enlarged. This test can also determine if you have an irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia).

- Coronary angiography is a part of cardiac catheterization. It lets doctors see your heart as it is pumping. Angiography can help identify a narrowed valve or any backflow of blood. This test also helps doctors decide if you need surgery, and, if so, what type. Also, this test can show if you have coronary artery disease.

- Chest magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can give a 3-dimensional picture of your heart and valves.

If you have valve disease, you should always tell your dentist, because you may need to take antibiotic medicine before a dental procedure. Whenever you are giving a doctor your medical history, remember to tell him or her that you have valve disease. Like in dental procedures, you may need to take medicine before surgery or other procedures. If you have valve disease and do not take antibiotic medicine before a dental or surgical procedure, you may increase your risk of developing an infection in the inner lining of your heart. This infection is called infective endocarditis.

- Digitalis, which reduces the workload on your heart and eases some of the symptoms of valve disease.

- Diuretics, which can lower the salt and fluid levels in your body. Diuretics also reduce swelling and ease the workload on your heart.

- Anticoagulant medicines, which prevent blood clots, especially in patients who have had heart valve surgery and have a prosthetic valve made of synthetic material.

- Beta-blockers, which control your heart rate and lower your blood pressure.

- Calcium channel blockers, which affect the contractions of muscle tissue in your heart. By lowering your blood pressure and reducing the workload on your heart, calcium channel blockers may put off the need for heart valve surgery.

Repair may involve opening a narrowed valve by removing calcium deposits or reinforcing a valve that doesn’t close properly. Repair may also be used to treat congenital defects and defects of the mitral valve.

Replacement is used to treat any diseased valve that cannot be repaired. It involves removing a defective valve and stitching in its place a prosthetic valve. Prosthetic valves can either be mechanical (made from materials such as plastic, carbon, or metal) or biological (made from human or animal tissue). Mechanical valves increase the risk of blood clots forming on the new valve. Patients with mechanical heart valves will need to take blood-thinning medicines (Warfarin) for the rest of their lives.

Valve surgery is an open heart technique. This means that surgeons use a heart-lung machine, because the heart must stop beating for a short time during the operation.